Published April 4, 2017, Los Angeles Daily Journal – There once existed a time when our teenage youth dreamt wildly of the car they someday hoped to own, adorning their bedroom walls with posters of European exotics and American muscle. Getting your driver’s license was as much of a rite of passage as any, exposing our budding generation to a cornucopia of opportunities, freedom and self-exploration.

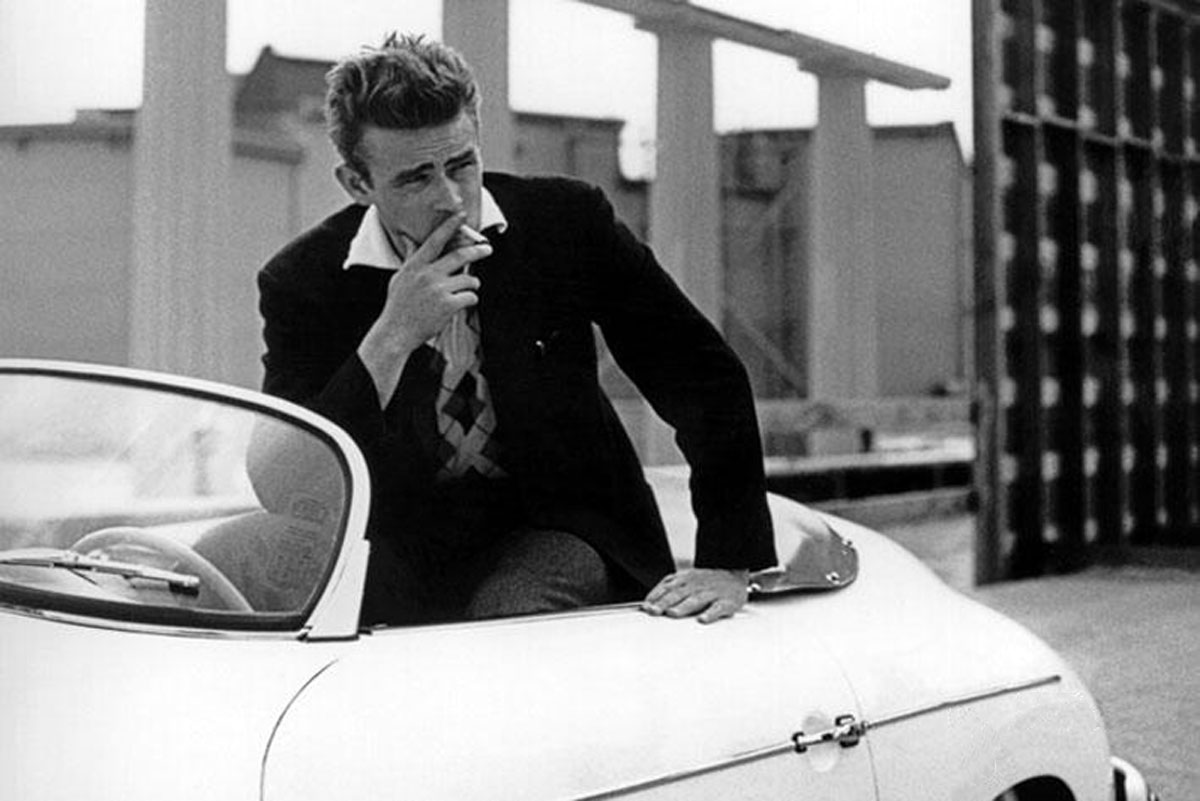

The last century has seen a nation routed in cars, whether it be because of the enormous utility they provided or the visceral emotions they invoked. Lost legend James Dean was known as much for the Porsche he drove as the three films he started in, as is true with Elvis and his Cadillac, Steve McQueen and his Ferrari, and a long list of other A-list celebrities.

Yet something has changed over the last decade, as social media has upended America’s love affair with the automobile. Millennials (those born between 1981 and 2000) have found a brave new world, hinged on constant connectivity and instant gratification. They don’t drive to the mall to shop and socialize, because they buy everything online and connect through an increasingly complex web of social platforms. Talking in person — in fact, talking at all — has been supplanted by texting, messaging and Facebooking; and the fact that “Facebook” (and, for that matter, Google and Uber) has become a verb just about says it all.

Empirical data shows just how far the country has digressed from the automobile. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, in 1978 50 percent of all Americans obtained their driver’s license by the time they were 16; by 2008, that number had dropped to 30 percent. In a recent study conducted by Gartner, one of the world’s leading information technology research companies, 46 percent of all those between the ages of 18 to 24 said they would choose internet access over owning a car.

Emerging platforms such as ride-share programs and autonomous cars are only serving to further the gap. To be sure, ride-shares and autonomous cars advance an enormous societal good. Ambulatory citizens and the elderly now have a convenient and inexpensive way to move about the world, and the number of drunk driving deaths that will be avoided will be staggering. Yet, for all their good, the advancements in technology have had a numbing effect on America’s passion for the industry.

Of course, none of this means that cars won’t be built, or that sales won’t take place. As our population continues to grow, so too will our need for cars. Expect, however, that more sales will be made for the purpose of fulfilling the ride-share needs, or for driverless cars altogether.

So prevalent has this become that economists are now conducting modeling called the “mileage crossover point” — a determination of when it makes economic sense to no longer own a car, and rely solely on ride-shares. Data from the Federal Highway Administration shows that Americans take an average 534 trips per year in their cars, and log an average 13,476 miles per year, with an average commute of 25 miles. Using Southern California Uber (non-surge) rates, taking Uber everywhere would cost $18,115 per year.

Weighed against this is the average cost of mid-size car ownership for the same miles traveled, which as measured by the AAA, is $8,876 per year. Car ownership is clearly cheaper than using Uber for everything, but that conclusion begins to change as the miles driven is manipulated — hence the mileage crossover point. For Southern California, the cross-over point is 6,500 miles, meaning that if you drive fewer miles per year than this, it is a better economic decision to avoid car ownership. As cars become more autonomous, avoiding car ownership will only become more attractive.

It is no surprise then that last month microchip giant Intel announced its plans to acquire the autonomous vehicle technology firm Mobileye for $15.3 billion — a purchase price that was 60 times Mobileye’s earnings. Ford is also jumping in the game, having announced at the 2017 Detroit Auto Show that it will be shipping “level four” autonomous cars by 2021.

SAE International, an engineering professional association, has developed a six-tier scale for automated driving, with level zero being no automation and level five being full automation. Ford CEO Mark Fields compared the automotive industry to the film industry, noting that Kodak missed the opportunity to reinvent itself as a digital film company that would embrace mobility.

It remains to be seen whether Ford will reach its ambitious goal, but it is apparent that autonomous technology is quickly becoming the gold rush of the new millennium. Goldman Sachs has projected that the market for autonomous vehicles will grow from $3 billion in 2015 to $96 billion in 2025 and $290 billion in 2035. Boston Consulting Group predicts that by 2035, 12 million autonomous vehicles will be sold globally.

While most agree that our future will be filled with autonomous vehicles, the road to get there will be complicated and thorny. Last September, the Department of Transportation issued a federal policy that was to provide guidance on the testing and deployment of automated vehicles. Yet, the policy was far from federal law, leaving the states to themselves to regulate the industry.

States have begun exercising this authority, resulting in patchwork legislation throughout the industry, with no clear definable direction. California also passed legislation last fall that allows autonomous vehicle testing if conducted at specified locations and the if vehicle operates at specified speeds. In December, Michigan enacted the Safe Autonomous Vehicle Act, which prohibits any company who is not a vehicle manufacturer (such as Intel) from testing self-driving fleets in the state. In all, eleven states have passed laws regulating autonomous vehicles.

As Generation Z (those born after 2001) begins to age, one has to wonder if their relationship with the automobile will have any resemblance to relationship experienced by the generations who came before, or if they will even care. To be sure, times are changing, and that is not necessarily a bad thing, just different. As aptly stated by Alexander Graham Bell, “When one door closes, another door opens.” Our door to the passionate relationship with the automobile is about to close; it remains to be see what will be behind the next door that opens.